We interviewed representatives of each of the Case Study Councils and learned of the story for each Council. Click on the respective Council logo to read about each of their experiences.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Our community copes with regular cyclones and is generally well prepared for natural disasters so it is always effectively on stand-by. But the pandemic lockdown and economic impacts were unique and very severe. It caused a major impact on tourism which destroyed some businesses. It also impacted detrimentally on the agricultural industry which is normally reliant on itinerant workforce that was suddenly no longer available.

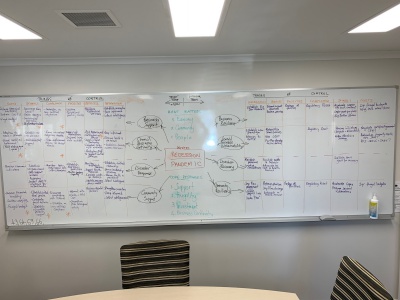

The Executive Leadership Team met weekly and made quick decisions. The Business Continuity Plan (BCP) Team also met regularly. Communication got better as time passed with seventy, Corona Updates passing on State Government information. There were also 69 safety alerts issues and regular updates from Chief Executive Officer (CEO) and the human resources section.

We complied with Chief Health Officer’s (CHO) Public Health Directives. We practised trial work from home days to make sure technology and other arrangements were in place. The greatest impact was felt in final months due to the short lockdowns. Closure of libraries resulted in stand-down of some employees. This was difficult and the organisation wasn’t prepared for it. Initially there was a lack of clarity on how to respond. We tried to redeploy staff which was relatively new to the organisation. Some staff were disappointed and felt there was a lack of consultation regarding leave provisions, work from home arrangements, back up for IT arrangements and safety requirements. However, working from home has been embraced and is now part of the workplace flexibility.

These plans were as effective as they could be, but the pandemic created a different context. The pre-existing plans weren’t necessarily pandemic related, but they still had some relevance. Rapid changes of CHO directives necessitate plan changes anyway. Our organisation was quite agile and capable of responding. It took the approach that it was about continuing to deliver all services where possible rather than just essential services.

Almost immediately. The Business Continuity Team (BCT) is able to convene by telephone to ascertain which components of the plans were relevant to the pandemic context.

It's difficult to ascribe a rank of usefulness to the plans as they each had individual, unique objectives. Perhaps the ongoing engagement itself with community was most useful, as it allowed Council to refine recovery efforts, and ensure that measures could become increasingly targeted.

For example, our 12-month progress report on the Cairns COVID-19 Local Recovery Plan specifically, ultimately revealed that the economic impact of the pandemic had been less severe than expected, but there remained significant concerns about community health and social wellbeing.

However, the tourism and international education sector continued to be significantly adversely impacted by travel and border restrictions. Further, access to affordable and secure housing remained one of the most significant issues affecting the community.

The research also outlined ongoing concerns about mental health, financial hardship due to loss of or inconsistent employment, domestic and family violence, and addictive behaviours.

For obvious reasons, the organisation didn’t have the luxury of a lengthy planning window, nor the ability to forecast the direction/impacts of the pandemic. However, the existing decision making framework of Council meant that we had capacity to be agile, and to pivot where required to meet needs.

When it came to assessing what those needs were, the Cairns Rapid Search and Needs Assessment was undertaken in partnership with James Cook University. Directly from that report:

“The Cairns region is identified as a high impact area for the consequences of COVID-19. Being a rural-regional location and economically being largely reliant on the tourism industry, its unique socio-economic characteristics has rendered it as ‘highly vulnerable,’ with significant impacts on the social, economic and emotional health of the local population.

Despite the regions vulnerability we have an opportunity to meet our challenges in new and innovative ways that build on the regions many strengths. Cairns Regional Council (CRC) has been proactive in developing and acknowledging local responses to COVID-19 and in building an evidence base to guide response and recovery strategies. CRC has partnered with James Cook University to undertake a Rapid Social Needs Assessment (RNA). The project has three primary aims; 1. To determine a rapid and preliminary understanding of the social impacts of COVID-19 experienced by the Cairns community; 2. Create and evidence-based response strategies to inform short term to medium -term recovery planning and investment priorities, accounting for lag effects and the potential for resurgence; and 3. The work will also inform long-term recovery information needs and planning.”

Panic buying was evident. Pockets of community were not accepting the Public Health Directives (e.g. vaccinations). There was a backlash from a noisy minority. It may have been different if the community experienced worse infection rates. The tourism industry and health industry were affected first and had to anticipate ‘worst case’ scenarios. There was some confusion seeing international stories but otherwise there was minimal public health impact locally.

It was a moderate reaction; planned and well considered. The priority was the economy and the need for business community support.

The reaction was varied. Some stressed but others relaxed. So the organisational response focussed on communication. Special pandemic leave was included in Certified Agreement for those in need. Timelines on closure impacts (e.g. Cairns Performing Arts Centre) caused difficulty in notification and communication. We had 120 redeployment cases. There were instances of staff offering to take leave rather than take a redeployment place. The vaccination mandate phase was distinct and caused some tensions.

Meeting room numbers were capped and social distancing, hygiene were the main preventative measures. We got better over time with mental health support and conducted training and provided online resources. We also promoted and maintained the Employee Assistance Programme (EAP) throughout.

A survey of representative of staff was conducted but it did not involve the whole of organisation. Communication was important. Some liked working from home and some didn’t. Flexible work arrangements defined a minimum of 2 days/week in the office. The policy changed due to flexible workplace benefits e.g. parent care of sick child. The Certified Agreement allows for individual 9-day fortnight arrangements. Prior to pandemic working from home was only available to senior management but it is now more widespread. Previous technological constraints have now been addressed. Staff pay for own internet etc. as an offset to commuting costs.

As mentioned earlier, the ongoing engagement with community allowed Council to continually refine and target measures.

Multicultural communications were established for disaster management. Council used media alerts extensively. The Local Disaster Coordination Centre (LDCC) was used for communications, too. Social media was also very useful.

Identified impacts of the pandemic included:

There were issues with hotel quarantine. State Government asked for Council’s Regulatory Services team assistance – denied unclear. Community protests were undertaken first about lockdown then later vaccination. Not likely to be much different to other protests.

Council;

Arguably the most impactful response (from an economic/business stimulus initiative response) was the acceleration of Council’s capital works program – namely the Cairns Esplanade Dining Precinct. The dual benefit of firstly being able to minimise impacts to traders with the disproportionately low volume of foot traffic due to the impacts of border closures, and secondly provide economic stimulus and act as a attractant for future domestic and international visitors, was of great effect. The added benefit was the impact to morale, given the utility and enjoyment for community members.

The level of collaboration and the speed of decision making were outstanding. The use of special purpose teams and committees to respond (e.g. BCP Team) was very effective. Assigning people with the right skills and abilities in the right tasks was crucial. Local networking with the local Hospital and Health Service (HHS) was also done well.

Managing ‘business as usual’ and responding to pandemic disaster simultaneously was very demanding. Perhaps better prioritisation might have mitigated this impact.

Approved by Mica Martin 1/9/2022

The pandemic occurred in two parts – no one was prepared initially but in the later stage when borders opened in 2021 the community was well prepared. It took 6-8 months to get ready but there were no cases in Cherbourg in that time so there was plenty of time to get ready.

Much the same as the community – there was not sufficient structure initially but later we got that into place. There were three key challenges – health; media; and resupply. For example, the first COVID-19 case was detected on 29 December at 1pm. In response, Rapid Antigen Testing was activated in town next morning! We tested 500 people in 3 days.

In accordance with the Business Continuity Plan (BCP), immediate conduct of meeting (management) was arranged Reference was made to departmental BCPs. Vulnerable staff were asked to stay home. Leadership examples caused the team to follow and perform well e.g. vaccinations. The BCP implementation was undertaken as a week-by-week approach e.g. the Indigenous Knowledge Centre was closed to stop exposure. Isolation and constraint of physical contact was the main safeguard. Exposure was not to the Delta strain, so the impacts were milder. As such, risk assessments were undertaken and we and responded accordingly. The Omicron strain emerged later and was mild as well.

The Biosecurity Act Determination by the Commonwealth Government was imposed on 18 March 2020. A checkpoint was installed straight away and operated by the Australian Defence Forces. This meant the community was immediately protected from Delta but there were significant implications e.g. mental health. Immediately after the first case, masks, testing, quarantine and resupply were imposed in sequence.

We had no resources to re-write plans so we will benefit from future better plans. There was a risk of over-reliance on key people.

At first there was panic when the checkpoint was installed. Thirty people fronted at the CEO’s office worried about isolation and impacts. The Cherbourg community was used to crossing into neighbouring areas to shop as needs rather than stocking up on daily necessities. This meant they were not prepared and did not have provisions. Revised checkpoint passes to allow a supermarket visit at Murgon were introduced to address this critical need. It took 6 hours to resolve but was essential to allow the community to access its needs. In our community behavioural patterns and lifestyle are not usually able to be changed overnight.

The elected members remained balanced and didn’t overreact. They stayed calm. This was assisted by open and honest communication each day with briefings. This remained consistent over the full period.

Key people living in community were important. Staff acted much the same as the broader community and were concerned at first. Frank and open communication was important and is part of the culture. Our staff were consistently prepared to pitch in (typical of the ‘no overtime’ culture).

Tragically there were 8 suicides (all aged 18-30) in the community which impacted heavily (5 in first 4 months). There was fear exacerbated by of images of international tragedy. Mental Health training was done with all staff. RUOK day was facilitated in response to traumatic losses. Yarning is a hallmark in our community’s culture. Very positive corporate communication was also essential. The message that Council cares was important. Social media and website reinforced positive messaging.

The role of a CEO as a human being was important during these times e.g. flowers for grieving family. Food Banks, Second Bite and Fair Share (NFP’s) provided truckloads of groceries within a day of the first case. Food was delivered to homes on the next day by Council staff. This was repeated with each event and demonstrated care by Council. It was challenging and important to identify who was in real need and the extent of that need. In the last drop we delivered 300 boxes which lasted over the month. Masks supply was most important which we distributed for free. Importantly this stopped spread of infection. Vaccination was the other key.

Images of the International tragedy and the suddenly imposed Checkpoint control combined to impact the community heavily. Media broadcasting had huge effect and media should bear some responsibility. It was very stressful for leaders in the community. A positive approach with honesty and trust builds and will be of value for the future. Floods since have demonstrated the community’s resilience. We travel as team currently from Wondai. There was considerable media interest and we gave a positive response every time; a strategy which worked.

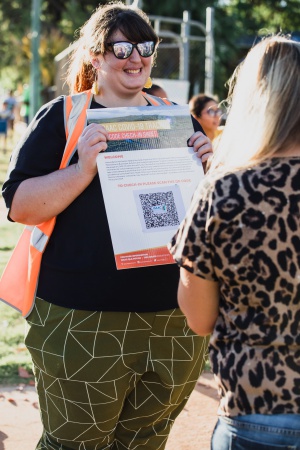

Disaster must be managed with positivity and hope in both culture and attitude. To address some resistance, the Police were out with megaphones encouraging wearing of masks etc. We have own community radio station which was important with its repetitive messaging. Social media was also effective (12000 Facebook followers). Our Ministerial Champion was also taken by the mayor house to house to encourage the community. We also conducted a full week of doorknocking to encourage vaccination.

Wearing of masks was no problem but social distancing in young people was a problem. Infection spread most at Christmas parties. Government directive was not clear regarding some events e.g. funerals.

Forcing First Nations people doesn’t work (lessons of the past). Education does work and messaging with care was critical to let them determine their own actions.

Communication and caring. Our relationships with other agencies were also very effective.

Insufficient documentation.

Approved by Chatur Zala 17/7/2022

We were not prepared for pandemic but well prepared for disasters. We have good disaster management plans and relationships and are well practised with cyclones and fires. We’ve also recently developed mass gathering protocols due to a sporting event fatality (Coroner’s recommendation).

We didn’t have pandemic in risk management plans but are experienced in disaster management. We were not prepared for direction of the Commonwealth Government. But we had no infection for two years. Cook had not been subject to a Biosecurity Act Determination (BD) previously. It was announced suddenly on 18 March 2020 and without apparent plans in place. It should be noted that access into Cape York is primarily by road and the determination meant that a physical barrier was abruptly placed across Mulligan Highway.

They did serve our needs with disaster management relationships/hierarchy recognised. However, they were not directly relevant to a pandemic. Rather they were designed for other natural disasters. The Local Disaster Management Group (LDMG) was in place but no distinct lead agency for the pandemic was evident at first. The Biosecurity Determination was made by Commonwealth Government, but Queensland Police Service (QPS) implemented and enforced it at the road and airport lockdown. The Chief Health Officer (CHO) and the Department of Health (DoH) ran separate to the LDMG as public health directives.

The Cape York closure also impacted surrounding Aboriginal Shires. The Torres and Cape Hospital and Health Service (HHS) is based in Cooktown. Cook Shire is not recognised as an aboriginal shire but includes some indigenous communities.

The Cape was locked down early by the Commonwealth Government so Cook Shire was forced to be an early developer of responses and procedures (including the first to establish entry application forms). The BD included reference to ‘essential worker’ so there was confusion as to who was affected due to very loose definitions. Council had to interpret and make assessment as to how to apply the BD and developed forms/procedures.

Council also established a dedicated call centre to cope with deluge of calls. We redeployed staff from other positions to respond. We had to capture questions and get answers and make referrals where appropriate. The Commonwealth Government initially was not ready or sufficiently prepared to respond.

Circumstances changed every few days. Quarantine was protracted for some weeks. A Quarantine Hotel was set up in Cairns. Circumstances such as pets, dying relatives, school holidays children, mustering cattle droves were not anticipated or understood by the Commonwealth Government. Medical evacuation was provided for some but not all with inconsistency. Many private patients elected not to travel to Cairns for essential medical treatment because they could not leave without return quarantine for two weeks.

Commuting workers couldn’t enter for work unless deemed to be essential workers, or re-enter after leaving for work (unless completed quarantine which was completely impractical for workers with families and other responsibilities and no funds).

This all took place between 20/3/20 – 15/7/20.

During this period, it moved under control of Queensland CHO. However, there was still the need for local interpretation as to whether or not to refer applications to the CHO. A small group comprising the Mayor, Chief Executive Officer and a QPS Officer met and considered applications on a seven day a week basis for approximately four months. This was very difficult and consideration of desperate applications e.g. newborn babies quarantined with families was stressful. They changed the rules and designated Quarantine Hotels. In one example a staff member was locked up with wife, new-born baby, 7-year-old and parents-in-law visiting from Philippines for say 6 weeks.

Change of information resulted in incorrect or outdated information circulating. We learnt of announcements mostly on TV. There was mixed messaging due to the Biosecurity Declaration (BD) application. The later ‘50km rule’ was a nonsense due to large distances between remote towns. Mayors of aboriginal shires were disadvantaged not being involved in approving applications for entry of essential workers and often did not know who was entering their communities. The whole thing was handled as a health issue not a disaster. Mental health, economic impact etc. also had to be considered.

The BD closure impacted small businesses severely e.g. hospitality industry. Domestic Violence and drinking increased. There was no telecommunication at BD roadblock (mobile blackspot). It took a 1-hour drive to get into mobile range. This made it particularly difficult if turned back at roadblock – where were people to go?

We were required to prepare plans but they became obsolete when the CHO took control due to ever-changing environment. Support from DATSIP in preparing plans was appreciated but otherwise no guidance was given in preparation of plans. Cook Shire’s circumstances were hybrid – remote indigenous communities and the mainstream economy of Cooktown. The BD captured the whole local government area though and therefore Cooktown locked down. Mixed messaging of indigenous priority was not consistent when it came to vaccination. Our communities were the first to be locked down but apparently some of the last to be vaccinated. But there were many, valid logistics issues.

Not really. Emergency Coordinators worked with LDMG’s. DATSIP was also involved. Agencies were not adequately integrated. Meetings were not adequately connected.

They did not think it was real. There were conspiracy theories and they questioned the need for lockdown. International news was considered irrelevant at first.

Reaction to Government action is more important to understand. The District Disaster Management Group Executive Officer (DDMG XO) advised on Saturday of lockdown and transition of a few days before 25 March 2020. Some were trapped out of community. There were many abusive calls to newly established Council Call Centre. There was then realisation of lockdown impact and confusion about ‘essential worker’ definition. Some then wanted to keep border closure for protection when it was proposed to be removed. People thought Council was making the decisions. Council had to make assessment on exemptions. In some cases, applicants went around Council and that undermined decision making.

This all occurred just before the 2020 election which had a late declaration of polls. The newly elected Council was in place in May 2020. There was some social media. Council’s organised response created some confidence. There wasn’t significant financial impact on Council. Councillors were generally comfortable that things were under control.

It was much the same as the community. There was some concern about job security and limits on communications. The Call Centre abuse was pretty bad. Staff were affected by hard stories and impact on their lives. It was very emotional for them. The team had to prepare procedures and forms and logistics on the weekend. Staff worked 7 days a week for over 6 weeks.

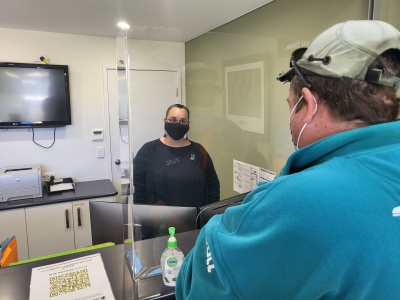

Social distancing, separation was a big part of our COVID-19 Management Plan. Staff helped each other. Some staff didn’t see their partners for 3 months. The Employee Assistance Programme (EAP) operated by Assure and presentations by the Royal Flying Doctor Service (RFDS) were important. Probably in hindsight we didn’t understand the pressures. But ours is a very resilient team. Offices were closed so customers sought help with travel application forms.

There were two main hurdles, minimal resources (information technology) and not everyone has internet connection at home e.g. the Lockhart internet and mobile reception blackspot. Workplace Health and Safety inspections of home offices were not always possible to establish office that meets requirements. We redeployed staff into other roles in lieu of working from home. We conducted a survey of staff identifying skills for redeployment. There was a limit on verbal interaction so reliant on emails. It was not sustainable for part time work from home and commuting if they live in say Cairns. People aren’t coming in from home when sick or constrained and this is tolerated more now. There was less spread of flu around office. Greater use of virtual meetings is a benefit with reduced cost and enhanced opportunity.

Grants were very successful e.g. business resilience. Twenty applications were received for wide range of needs including PPE, hand sanitisers, digital business initiatives. Some businesses changed operation e.g. food deliveries (in absence of fast food and home delivery). Our ‘Buy Local’ campaign was big. The LDMG activated the ‘economic recovery group’ and worked with the Chamber of Commerce. The Facebook page ‘Cape York Connect’ facilitated business networking, provided information and served as a sounding-board for the community. Our Call Centre played such a huge role e.g. event organisers sought lots of advice and assistance. Post lockdown we are still seeing same support.

We have several diverse communities so it’s not all about Cooktown e.g. messaging when proposed lockdown of Coen. Community-specific COVID-19 Plans were developed. The big event mid 2021 Cooktown and Cape York Expo was rejigged to be a Recovery Event with live music, regional arts showcase, business symposium. It was really important for community – perfect timing.

There was uncertainty of the BD application and angst within community wanting to come in and out of Cape. There was also uncertainty in surrounding Aboriginal Shire Councils. Different information confused the community and changed sometimes daily. So the challenge was to establish one source of truth.

There was no ‘lead’ agency due to Commonwealth and State agencies with different roles dependent on Cook Shire being in the middle. There were lots of rumours (social media) which caused further confusion. The CHO and Premier announcements were not foreshadowed. People were affected socially and mentally. There was a lack of understanding by other Governments of the importance of this issue. Some private medical patients were prevented or made difficult (return quarantine) to get treatment. People put their lives on hold and South-East Queensland (SEQ) did not understand this. Medical and dental services etc. are limited in the Cape so SEQ underestimated the impact on lack of access to such services that might be taken for granted. There was no system to deal with these. The BD quarantine requirements made it inhibitive, unlike border bubble exemptions on State borders.

Some did fight the Public Health Directives (PHDs) e.g. there was vandalism of barriers. People who had court orders (family custody) caused difficulty. Council facilities managed compliance e.g. café run by Council. People rudely treat staff. Environmental Health Officers (EHO’s) were required to enforce but the size of the jurisdiction and limited resourcing (1 EHO across entire Cape York) meant it was not feasible.

There was also a question of legal authority for QPS enforcement. DoH did do some enforcement checks of business compliance. QPS enforced the BD directive (without authority?). Australian Defence Forces (ADF) presence as well may have addressed this. It was difficult to enforce community activities and events e.g. rodeo race days. Community was disappointed that some events could not be delivered. There was a constraint on insurance coverage due to camping risk of COVID-19 compliance. Cooktown races was a big test. Preparing the Compliance Plan requirement was onerous (e.g. 48 pages for the EXPO). Council’s event EXPO 2021 compliance cost extra $80k.

Council did have some Influence in Coen. Council officers went there to boost vaccination uptake. They personally visited each house door to door with DoH nurse to encourage vaccination. Some said no but most did and found it convenient. Out Government Champion got funding to incentivise vaccination. A Christmas event was conducted (Sunset with Santa) in Coen with jumping castle; a first for Coen. We relayed CHO messaging. Subsequent vaccination enquiries came from some communities, so a clinic was arranged. We worked with DoH to get message out.

Refer earlier responses. We also conducted a survey of businesses and community with the Queensland Reconstruction Authority (QRA).

The Queensland State Government COVID-19 Call Centre didn’t know where Cooktown was!!! Wrong advice was given to tourists.

The way that staff came together on the first weekend (12-15) to handle the situation caused by lockdown. Flexibility, willingness to work together and treat it as a priority. They were quick to adapt and learn. IT staff set up of Call Centre. Whole of Council effort. LDMG daily meeting (7 days/week) to assess applications but supported by the collation of information and triaging of applications in such an orderly fashion. Record keeping task was also onerous and developed on the fly but essential. Communication with neighbouring Councils, QPS etc. was significant. High level of trust important. Staff flexibility was excellent. No one complained. Staff compliance was also very good they were role models for community e.g. vaccination uptake.

Difficult and stressful operation of Call Centre. Maybe more pro-active support would have been better. Some staff worked continuously for a few weeks which was a risk to staff well-being. But got the job done and supported each other where required.

A pandemic not catered for – not prepared – not expected. Our Council was well prepared for and experienced in responding to other natural disasters e.g. floods predominantly and bushfires but not a pandemic.

Our Business Continuity Plan (BCP) was adequate, but it did not prescribe a response specifically for a pandemic. Internally we had discussed the prospect of a pandemic twelve months prior, but it was not expected realistically. However, ours is a stable organisation with healthy dynamics and a good culture in the workforce, which stood us in good stead.

Our existing plans were pretty good. The BCP dealt with the event and our Disaster Management Plan was adequate. We stood up the Local Disaster Management Group (LDMG) immediately after the first border closure. There was significant communication with relevant agencies. Other councils reflected on our LDMG standing up and followed (neighbouring councils initially). The Department of Health’s local Director of Nursing (DON) was also very active.

The BCP was activated right from the start. The LDMG and Recovery Plans were activated after the first border closure when the potential of their full impact was realised.

A Workforce COVID-19 policy was put in place April 2020. Union representatives were involved early. The Policy was developed internally and was checked by our legal team. An Information Technology Policy and Recovery Plan was also established.

Our communities were not heavily impacted at first (except for retail/hospitality during first lockdown and border closures). Social media resonated from international news (e.g. Italy). The community was not traumatised but frustrated mainly about border closure (imposed by Queensland State Government) and different interstate rules. Some of the border closures occurred right on key farming season times (e.g. harvest). In particular the closure of the latter half of 2021 impacted which was to be the first harvest post drought which had a practical impact on the farmers and transporters, especially on workforce and supply of inputs and services. The border passes and the process of crossing the border also caused confusion and frustration.

Our leaders reacted promptly. Our Mayor took the lead role in media. The community lobbied our Mayor, then the Mayor advocated strongly to the State Government. The Mayor also led the vaccination rollout. Community expectation was directed at Council in lieu of State Government. Because Council was seen to have advocated well, further expectations arose.

Staff were not as frustrated as community. As CEO I spoke with employees early regarding the situation and new Workforce Policy. A Department of Health representative participated in these discussions. Questions were encouraged and issues were dealt with promptly. Staff maintained a calm posture throughout the experience.

Education, communication, work from home, personal protective equipment (PPE), hygiene/disinfection materials, ‘Perspex’ screens at customer service were all employed. The Workplace Health and Safety Officer spoke with Customer Service Staff. Council allowed time for staff to get vaccinated and we promoted the Employee Assistance Programme (EAP) for employees which maybe could have extended to families of employees.

The experience overall was pretty good. We identified work from home candidates rather than facilitating voluntary work from home. About a dozen employees worked from home. The criteria included vulnerability (in a sensitive manner) based on age and known health conditions, as well as the vulnerability of close family members that they reside with. Staff were able to raise concerns so vulnerability could be exposed if they wanted. This has opened a new perspective on work patterns.

The vaccination set-up was the Mayor’s initiative. The community responded well and had highest rates compared with other communities. Staff lead by example. Webinars were conducted throughout. The last webinar included police, health agencies etc... Webinars were also conducted for business community. Fifty participants participated in each webinar. These were also recorded and put on Council’s website. Each webinar usually went for an hour.

We became adept at reading Public Health Directives. The early ‘border bubble’ was based on postcodes. Decision makers didn’t consult with Council and didn’t know the local circumstances. The last border closure impacted staff work movements. ‘Essential worker’ definition differed between Queensland and New South Wales (NSW). This impacted farmers and their workers. There was a lot of angst about crossing the border. Border checkpoint officer attitude impacted experiences and interpretation of the directives was sometimes inconsistent. Queensland Police Service (QPS) and Department of Health (DoH) communication was not always timely. Council maintained regular contact with the Police Station Officer in Charge.

Our area includes 300km of State border. Called “e-gates” an internal initiative was created by an employee and the idea put to QPS. The innovation involved Bluetooth operated locks which could be opened remotely. Cameras monitored the gates. It was designed for those with genuine local community interest. Applications for lock codes were made to Council and approved by the Police.

State Government information was not contextualised enough so Council did that. For example, announcements about sewerage test results by DoH frightened the community, but the likelihood that travelling public caused it was not stated.

Council copped the brunt of frustration when decisions being made by State Government impacted the community. When NSW had high infection rates it caused division in the community. There were heated engagements in the community caused by border constraints. Social media was very active.

We had no issues as evidenced by an internal audit compliance check.

We issued media releases and promoted it on social media. The DoN also did that. Our Mayor attracted high level of media interest.

They were quite effective.

They were generally all effective and were appreciated. Pedestal sewerage charge discount was appreciated by the hospitality sector. Rates deadlines were extended. Development application fees were reduced. Webinar grant application information was appreciated and was mainly intended to connect businesses with sources of further information. We are proud of facilitation of discussion and information sharing.

The fact that we operated as a united organisation was best. The dynamics of organisation supported the efforts.

We should have included pandemic in the Disaster Management Plan and BCP.

Would like to have more effectively deflected or referred community concerns to the State Government – not sure how though.

Our communities had limited preparation if any, being reliant on the government’s health system which had inherent weaknesses. However, the communities did possess built-up resilience through previous disasters. Rural and remote settings also create element of self-reliance. The mining sector also appeared to be unprepared, developing plans on the run.

Similarly, our organisation had limited preparedness if any. Council’s Business Continuity Plan (BCP) was under development and neither completed nor tested. Even if it was complete, potentially it might not have covered this scenario. It should be noted though, that organisation did have a strong response process with established Committees, communication channels, flexible work arrangements and specifically an IT system that allowed for immediate working from home (WFH) arrangements. Experience in dealing with adversity and the solid culture of the organisation meant that it was also prepared for an appropriate response to disaster management protocols.

The Disaster Management Plan (DMP) did have a section relating to potential pandemic events but it was largely reliant on the State Government’s Department of Health (DoH) as the lead agency. The DMP document did provide a solid baseline to then adapt and update to this event.

Council’s (internal) Emergency Management Plan (EMP) with its organisational focus was very useful and underpinned the allocation of roles distinct from the (external) DMP. The EMP had only been adopted in recent years and was to some extent still developing. The pandemic event (and other natural disasters) accelerated the finalisation of the system.

The draft BCP was of limited use as it was incomplete and not practised. Base principles were used to develop COVID-19 specific “contingency plans” for overarching and specific areas. This has then been used to update and adopt the BCP. The organisational culture helped to get through it. The pandemic forced us to think out of box with the BCP and information technology resilience.

Immediately (March 2020).

These documents served extremely well and assisted decision making and managing services and staff. All aspects were useful as they were developed with a practical approach and were readily flexible to update. Formal and documented risk assessment was undertaken for Unit Contingency Plans to identify ‘essential’ services and employees. This format was able to be transposed later into BCP. We took a very practical approach developing, implementing and testing as we went under the auspices of the Emergency Management Committee which met frequently. Double disaster event planning was also undertaken in case a natural disaster occurred in parallel with the pandemic. The Unit and Organisation-wide Contingency Plans were endorsed formally by Council on 26 March 2020.

Yes, this comprehensive documented framework was the foundation for Council’s entire response to the public health and economic risks that we thought the pandemic and recession might bring. It was developed immediately and was adopted formally by Council on 26 March 2020. It covered all aspects under Council’s control both internally and externally and set out the potential activity in both ‘Response’ (tactical) phase and the ‘Recovery’ (strategic) phase. The Recovery aspects of this initial framework were substantially developed over ensuing months.

The development and adoption of the framework was very timely and very solid and ensured that Council, its employees and its communities could have confidence that the situation and the outlook were being well managed.

Council’s Strategic Recovery Plan contains 50 separate strategies in line with a strategic recovery framework responding to:

The Isaac communities (8 towns across a vast 58,000sq km) were mostly accepting of the response required, noting that with a high mining resource population there was angst about the management of restrictions. Negotiations were held with relevant stakeholders to support the ongoing operations of the mines (ultimately playing a huge role in the nation’s economic resilience), implementing specific restrictions and guidelines. Council’s focus was to support the government’s directions. But because there had been no outbreak there was some reticence in community.

Council’s leadership enabled the disaster management response. Council readily and confidently adopted Strategic and Tactical Pandemic and Recession Framework and a number of significant initiatives very early. Council workshops were also progressively conducted to review and update relevant plans, and to develop new plans where gaps existed. Council supported and maintained service delivery through enabling staff and services with flexible systems (IT) support. The Mayor and Deputy Mayor pursued strong and continuous advocacy on behalf of the community regarding the implications of FIFO movements and several other important considerations.

The majority of staff responded positively to continue to achieve operational effectiveness. There were a small number of employees that due to underlying health issue had some concerns. Outdoor staff worked on while those that could, worked from home.

Council already had well-established protocols for wellbeing and safety initiatives, however, this further evolved with the development of tools and information to assist staff. Many new initiatives were immediately implemented such as regular messaging and updates, daily roll call, absentee mapping, well-being declarations, health check-ins, case management of vulnerable employees, publishing of FAQ’s, publishing of procedures for social distancing and hygiene precautions, creation of COVID-19 special leave provisions, adoption of a financial hardship support policy, regularly updated supervisor guidelines and working from home (WFH) tips.

Overall, our employees responded very positively. Health check-ins involving a personal phone call from the HR or safety team were done for all employees (even the CEO). Council’s ‘SMART’ phone and internet application (WHS system) was commissioned to allow employees to submit to a daily roll call register their state of COVID-19 health risk at all times and to declare any risks (e.g. travel outside of the region). Operational leadership team meetings involving over 100 supervisors and managers from across the region were held regularly by videoconference to engage and inform. Regular messaging from the Chief Executive Officer and Mayor was also conducted using SMS alert messaging to all employees’ and Councillors’ mobile phones.

This was established immediately when the first Public Health Directive stated that “those who can work from home should work from home”. A framework with tiered triggers and actions was quickly established and published by the Emergency Management Committee (EMC). Up to 200 out of 450 staff worked from home for several months (including the Mayor and CEO). WFH was relatively easy to implement due to our already sophisticated IT and remote supported systems. Guidelines were enhanced and developed to improve the protocols required for WFH arrangements. Each employee working from home was required to prepare and report on their individual work plan (including the CEO).

Following the major period of WFH, a survey of staff and their supervisors indicated positive experiences of WFH. It is noted that some employees resisted returning to work after WFH. As a result, the WFH or flexible workplace arrangements have been tested, challenged and somewhat increased with adoption of a new Policy. The residual change will be long term, however, there will be some learnings and tweaks as part of reviews.

On 26 March 2020 Council adopted a suite of initiatives as elements of the ‘Strategic and Tactical Pandemic and Recession Response Framework’, including the ‘Community Support and Wellbeing Package’ along with the ‘Business and Community Support Compliance Response Package’ and the ‘Business Support and Initial Stimulus Package’. The Community Support and Wellbeing package included measures to immediately address the following:

Sourcing timely and reliable information to share as sometimes advice from other levels of government was not clear or consistent requiring interpretation. Community lethargy in pockets was a challenge as Isaac did not experience outbreak for some time. Distinct communities reacting differently and having different access to services.

Yes certainly. Strong and persistent advocacy to State Government and the resources sector (direct to major miners and the Queensland Resources Council) was undertaken by Mayor and Deputy Mayor (involved in high level working group convened by Queensland Resources Council). This was naturally driven by strong local community concerns due to high exposure of itinerant FIFO workers from Southeast Queensland and interstate. Partly as a result of this advocacy special arrangements and rules were made for mining camps and operations. There was some reluctance at times by mining companies to share information. To illustrate the extent of the FIFO activity with high volume of travel into Moranbah airport it was reported that at one time it was receiving higher passenger numbers than Tullamarine Airport. On the very positive side, testing and vaccination clinics were provided by BHP for a significant period; thought to be necessary due to limited health services.

Council supported the State Government agencies in their role, through sharing communications and enabling access to agreed points of truth. Also, communications from the Mayor were timely and influential to support and inform the communities. We also provided local knowledge and ideas to the local Hospital and Health Service (HHS) and the District Disaster Management Group (DDMG).

This relates to the unilateral devolution of responsibility to Council’s environmental health officers. It was related specifically to take-away food from premises that may not have done this previously or different operations (delivery). We also prepared some different instruments of appointment for the short term for officers to do certain tasks.

Council supported by sharing of DoH communications and service delivery planning. Council also advocated through channels to improve accessibility and supplies for geographically diverse and disparate communities. The Mayor and Councillors lead by example. The communities generally gathered knowledge from their respective Councillors and leveraged off local events.

On 26 March 2020 Council adopted a suite of initiatives as elements of the ‘Strategic and Tactical Pandemic and Recession Response Framework’, including the ‘Community Support and Wellbeing Package’, the ‘Business and Community Support Compliance Response Package’ and the ‘Business Support and Initial Stimulus Package’. The Business and Community Support Compliance Response Package immediately addressed the following;

Adaptability and willingness of all levels of organisation to work together. Solution orientated rather than negative with a well-structured framework. Disaster management (external) and emergency management (internal) each respectively worked well but integrated effectively also. Information sharing and frequency of engagement was also strong.

Limited if any prior business continuity planning and testing, noting however that it was not likely to have addressed a pandemic scenario. Disaster Management Plan also included minimal pandemic planning.

Broadly, community preparation for natural disasters is familiar, but not specific to pandemic. We didn’t realise how much it would impact daily routines and access/movement. It came as somewhat of a shock to community. Some people adapted well and some pushed back.

Similarly, the organisation’s preparedness was a reflection of community. The Business Continuity Plan (BCP) system and understanding was in place but early on the Business Continuity Management Team (BCMT) has some “rabbit in headlight” moments. After the initial shocking realisation, to credit of organisation. people got on with it. Some parts of business facilitated success e.g. Executive Leadership Team (ELT) and the Information, Communication and Technology (ICT) Dept The organisation placed 90% of staff within 10 days into working from home (WFH) and established a dedicated call centre (100% off-site). Novel solutions were found for teams that could not WFH. This resulted in a cultural revolution regarding the flexible workplace.

These documents facilitated a ‘warm’ start but adaptation was necessary. There was no pandemic sub-plan. BCP and Disaster Management (DM) were maintained as separate operations but operated in parallel at start of COVID-19 response. The Local Disaster Management Group (LDMG) and the BCMT were both activated for a long period.

There was immediate activation. We stood up the Local Disaster Coordination Centre (LDCC) when the potential impact was evident. This was in part driven by the State Disaster Coordination Centre (SDCC).

‘EMBARC’ the home page for Council information was maintained specifically for COVID-19. The People and Safety Team and the Enterprise Risk Management Team did much of the work. Content was developed progressively and then reviewed for efficacy. EMBARC was first published in about April 2020. Council also produced its “COVID-19 triggers and response activity guidance” document which relates to Metro North Hospital and Health Services (HHS) three-tiered response framework in its published Pandemic Response Plan. Queensland State Government’s Department of Health (DoH) being lead agency in Disaster Management framework which was in contrast with normal hierarchy for other disasters.

Some decisions made by DoH without apparent consideration for local impacts on councils and communities caused difficulty. The community looked to Council, but it wasn’t privy to the decisions and didn’t have forewarning. The HHS and the State Health Emergency Coordination Committee (SHECC) didn’t let Council know when tiers were triggered. Council had to chase the intelligence. HHS and SHECC were apparently under-resourced. The Disaster Management Act hasn’t changed so these issues haven’t been able to be changed in Local Disaster Management Plans. Concepts also apply to disasters which transcend geographic and functional jurisdictions.

See also Q 5. Documents were endorsed by the BCMT whose Chair is the Director of Finance.

There was significant pushback in the community which manifested as abuse by customers (in business and Council interfaces). There was some shocking behaviour by a minority of the community. The broader community reacted better and there was good cohesion in some representative groups (e.g. indigenous groups).

Elected members were really forward-leaning. They implemented the ‘Emergency Stimulus Package’; a $15 million stimulus package to assist residents, community groups, community clubs and businesses experiencing financial distress due to Coronavirus (COVID-19) impacts. This included; $7m in rates relief, $5m in grants to community organisations, $2m accelerated asset maintenance works, and $1m refund food licencing fees. The Mayor and Councillors explored options very early and quickly established support.

After initial BCMT direction everyone got on board quickly and adapted well.

The Employee Assistance Programme (EAP) and other support mechanisms were promoted. A Pandemic Leave Policy adopted for exceptional circumstances. Work from home financial impacts on staff were also considered. All departments played their part. Service delivery was maintained. Toolkits assisted to inform support staff. EAP confidential counselling was maintained throughout. The ‘Mates in Construction’ suicide prevention programme was also used. Leader support hotline established through Acacia (EAP).

Where possible, teams encouraged to work in bubbles so infection spread would be mitigated. This was especially important for those who could not work from home. Social distancing in workplaces was maintained, including in vehicles.

A lot of staff faced intimidating circumstances. Staff were supported and security contractors were engaged at main customer interface e.g. libraries. Signage asking for respect to staff were also erected.

The majority of administrative staff worked from home (WFH) from 10 days of the pandemic starting. There were, however, some workers defined as ‘essential worker’ and there were those who could not practically work from home. The call centre was established with 100% WFH. Council is now more flexible workplace. A Flexible Working Policy was being put in place at start of pandemic, but it is now part of the culture.

Council adopted the ‘Emergency Stimulus Package’ which included a $15 million stimulus package to assist residents, community groups, community clubs and businesses experiencing financial distress due to Coronavirus (COVID-19) impacts.

Loan periods were extended and adapted to be done remotely. A ‘no contact returns’ process and items quarantined were all before being touched by staff. Gloves were used. Loan requests were also done remotely. Staff called vulnerable members of the community and worked with other agencies. Outdoor options were taken up where possible. Remote options were also generally preferred.

The Council website included a ‘Dashboard’ approach with referral to Government information websites. Community engagement teams integrated with community organisations and agencies.

We provided updates on Council’s website regarding Public Health Directives (PHD’s).

A light touch was preferred and employed.

The Council’s ‘Emergency Stimulus Package’ was adopted by Council on 25 March 2020. This included $7m in rates relief, $5m in grants to community organisations, $2m accelerated asset maintenance works and $1m refund food licencing fees.

Relationships were generally collegiate but the biggest challenge arose from government release of information and decisions made before Councils knew about them. This put Council on the back foot. The State Government’s Department of Health (DoH) website was not up to date, hence Council’s referral of information was also outdated.

We could have used a confidentiality agreement to enable sharing of sensitive information (medical in confidence). Council is always the community interface and takes the brunt of community pushback. State Disaster Management arrangements need to be revised for circumstances where the lead agency is a Government Department like DoH.

The responsiveness of staff at all levels was magnificent. Challenges of business continuity improved. The Moreton Recovery Plan emphasised the importance of planning and resourcing for the recovery phase of disaster management which demonstrated benefit in a recent flood disaster event.

Interaction with State Government agencies and DoH, and the coordination of public messaging.